BMI Guide Basics: What Is BMI?

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a simple ratio that relates weight to height. It is widely used as a population-level indicator to group adults into general weight categories. While BMI is easy to compute and compare across groups, it does not directly measure body fat or health. Think of BMI as a quick context marker—not a diagnosis.

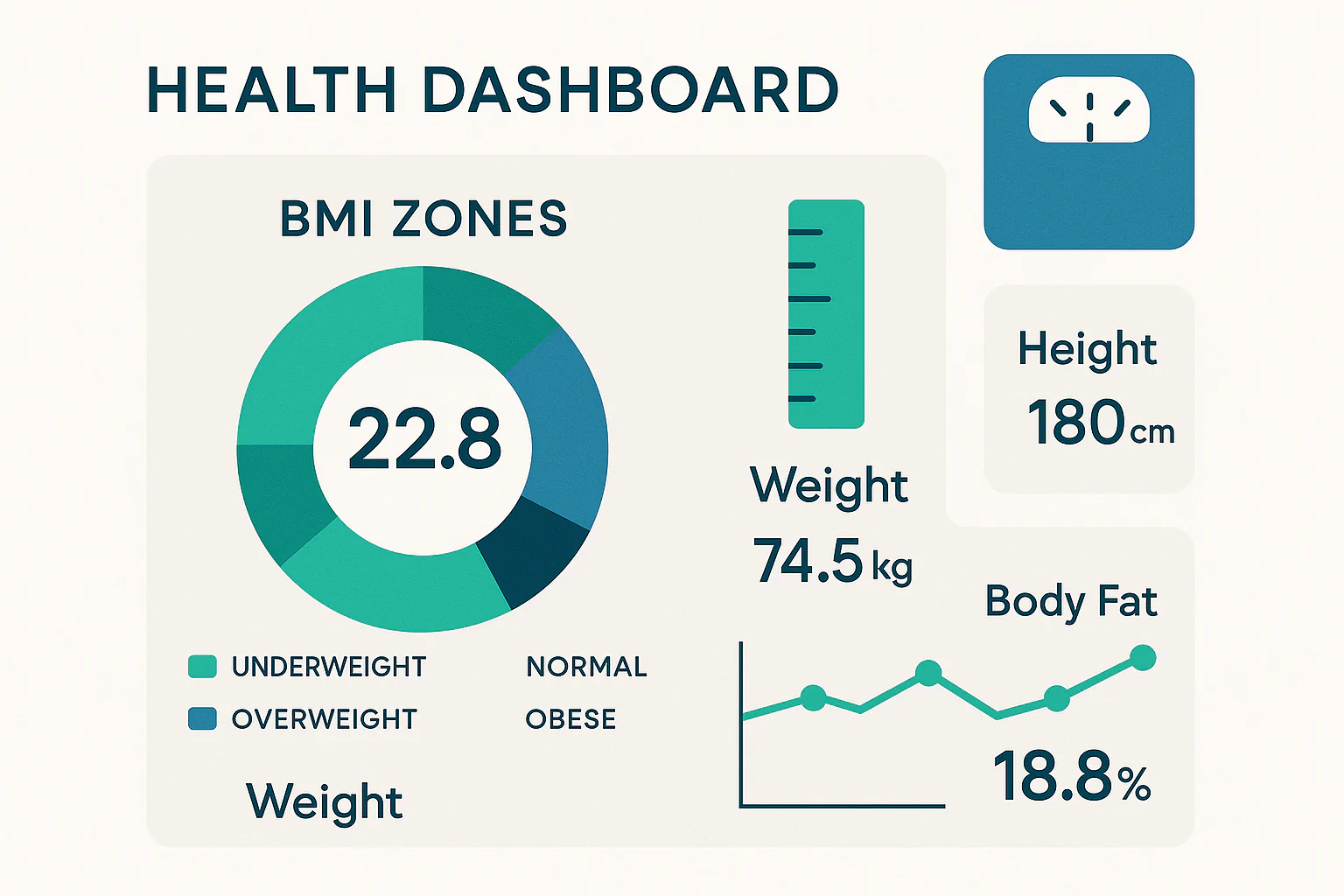

If you want to calculate your BMI right now, try our Adult BMI Calculator. For extra context, pair BMI with body fat percentage or waist‑to‑height ratio.

BMI and Health Outcomes: What Research Shows

Large population studies show that cardiometabolic risk tends to increase as BMI moves from the normal range into the overweight and obesity ranges. This is a trend across groups—not a diagnosis for an individual. Age, cardiorespiratory fitness, sleep, smoking status, and fat distribution all influence risk at a given BMI.

Central adiposity (more fat around the abdomen) carries additional risk. That is why pairing BMI with a waist measure improves context. Use our Waist‑to‑Height Ratio Calculator or Waist‑to‑Hip Ratio Calculator to get another lens beyond a single BMI number.

Weight‑neutral habits that help

Regardless of BMI, regular walking, two to three weekly strength sessions, balanced meals rich in protein and fiber, consistent sleep, and not smoking improve health markers—even when scale weight changes slowly.

How to Improve BMI Safely

Small, sustainable changes

Most people do best with gradual change. Consider a modest calorie deficit, prioritize protein, and keep weekly movement high. Our tools can estimate targets: Calorie Calculator, TDEE Calculator, and Weight Loss Calorie Calculator.

Keep muscle with strength + protein

Preserving lean mass matters for health and performance. Include resistance training and spread protein across meals. Estimate a daily target with our Protein Calculator.

Expect normal fluctuations

Water, sodium, and routine can shift scale weight day to day. Look for multi‑week trends. Prefer ranges instead of single numbers? See the Healthy Weight Range Calculator for gentle context.

When to Seek Professional Advice

Talk with your clinician if BMI changes rapidly, you have unintentional weight loss, or BMI and waist measures rise with symptoms like shortness of breath, daytime sleepiness, or reduced exercise capacity. A professional can personalize next steps.

This BMI guide is for information only. Health decisions are best made with a clinician who knows your medical history.

Conclusion

This BMI guide shows how to calculate your BMI, what the categories mean, and where BMI is most and least helpful. Combine it with body composition and waist measures to get a fuller picture of health context—and use tools that support sustainable habits.

How BMI Is Calculated

The formulas

Metric: BMI = kg / (m²). Imperial: BMI = 703 × lb / (in²). The result is a single number that can be compared with adult categories. For example, a person who weighs 72 kg and is 1.75 m tall has a BMI of 23.5.

Units and rounding

Most references report BMI to one decimal place. Use consistent units (either all metric or all imperial) to avoid conversion errors. Our calculator handles conversions automatically.

Worked Examples (Metric and US)

Metric example

Weight 72 kg, height 1.75 m: BMI = 72 / (1.75 × 1.75) = 72 / 3.0625 = 23.5. This falls in the normal range for adults.

US (imperial) example

Weight 180 lb, height 70 in: BMI = 703 × 180 / (70 × 70) = 126,540 / 4,900 = 25.8. That is near the lower end of the overweight range.

Measure Correctly to Reduce Noise

Small measurement differences can shift BMI by a few tenths. To improve consistency:

- Weigh at a similar time of day, in similar clothing, on the same scale.

- Measure height without shoes, standing tall against a wall with a flat object on the head.

- Track trends monthly rather than daily; day‑to‑day water shifts are normal.

- Pair BMI with a waist measure for context; see waist‑to‑height ratio.

Adult BMI Categories and Interpretation

For adults, standard cutoffs are commonly used to group BMI values into weight categories:

- Underweight: BMI < 18.5

- Normal weight: 18.5–24.9

- Overweight: 25.0–29.9

- Obesity: ≥ 30.0

These ranges are intended for broad public health guidance. Individual risk varies by many factors— including age, muscle mass, fat distribution, family history, and metabolic markers.

Reference: see CDC guidance on adult BMI categories here.

Limitations of BMI

What BMI does not measure

BMI does not measure body fat percentage or where fat is stored. A muscular athlete may have a BMI in the overweight range despite low body fat, while someone with central adiposity may have a BMI in the normal range but higher metabolic risk.

Populations where caution is needed

- Highly muscular individuals

- Older adults with sarcopenia

- Different ethnic groups with different risk thresholds

- Pregnancy and postpartum

- Children and teens (use age‑ and sex‑specific BMI percentiles)

Because BMI is a screening tool, clinicians combine it with other measures such as waist circumference, blood pressure, lipids, glucose, and lifestyle factors before making decisions.

Alternatives and Complementary Metrics

A balanced approach combines BMI with one or more of these tools:

- Body fat percentage — estimates composition directly.

- Waist‑to‑height ratio — screens central adiposity risk.

- Waist‑to‑hip ratio — another lens on fat distribution.

- Ideal body weight — a historical context marker (not a target for everyone).

- Lean body mass or FFMI — highlights the muscle component BMI can’t show.

For a thorough discussion of use cases and limitations, see the WHO overview on BMI and obesity epidemiology here.

Children and Teens: Use Percentiles

Pediatric BMI is interpreted using age‑ and sex‑specific percentiles, not adult cutoffs. If you’re checking a child’s number, use a dedicated tool such as our Child BMI Percentile Calculator and discuss results with your clinician.

Putting BMI to Work: Practical Tips

Use BMI for trend context

Track BMI occasionally over months, not day‑to‑day. When tracking goals, try to measure under similar conditions to reduce noise—same time of day, similar clothing, and the same scale.

Pair with meaningful actions

If BMI rises into the overweight or obesity ranges, consider practical steps: balanced nutrition, more activity you enjoy, and better sleep habits. Small, sustainable changes compound over time. Our calculators can help you plan: calorie calculator, TDEE calculator, or protein calculator.

BMI Guide: Read Your BMI with Context

Two people with the same BMI can have very different body compositions and risks. Compare your BMI with waist measures and lifestyle factors, and consider tools like healthy weight range for a broader picture.

Talk with your clinician

Discuss results—especially if changes are rapid, you have symptoms, or you live with chronic conditions. BMI is one data point in a bigger picture.

BMI Across Ages, Sex, and Backgrounds

Older adults and muscle loss

With age, many people lose skeletal muscle and strength (sarcopenia). Two individuals can share the same BMI while having very different muscle mass. In older adults, a BMI near the lower end of the normal range can sometimes coincide with reduced muscle and functional reserve. Pair BMI with grip strength, walking speed, and a simple waist measurement to get more context about body composition and independence in daily activities.

Sex differences and fat distribution

Typical fat distribution differs by sex and hormones. People who carry more abdominal fat often see higher cardiometabolic risk at a given BMI than those who carry more fat in the hips and thighs. Because BMI alone cannot distinguish these patterns, combining it with a waist‑to‑height ratio adds helpful context without special equipment.

Backgrounds and body composition

At the same BMI, average body fat percentage can vary across populations due to differences in height, frame, and composition. That is one reason guidelines sometimes recommend population‑specific cutoffs or complementary measures. Use BMI as a quick screening tool, then layer in other measures or professional evaluation to guide decisions.

Children and teens use percentiles

For children and adolescents, BMI is interpreted using age‑ and sex‑specific percentile curves rather than adult cutoffs. Growth, puberty, and development change the picture quickly, so a pediatric percentile calculator provides the appropriate context for that age group.

When a Small BMI Change Matters

Day‑to‑day BMI movement is mostly noise from hydration, meals, and measurement timing. Small, sustained changes over weeks to months can be more meaningful, especially when they align with changes in waist measures, fitness, energy, or lab values requested by your clinician. If a small but persistent uptick moves you into a new category, review sleep, stress, and activity patterns first—simple improvements often create measurable progress without extreme restriction.

Track simple, steady signals

Combine BMI with a morning waist measurement, a brisk‑walk heart‑rate check, and a weekly activity total you can sustain. These signals change more slowly and help you focus on habits rather than day‑to‑day scale variation.

Use BMI to inform, not define

BMI is most useful when it prompts the right questions: How am I sleeping? Am I moving regularly? What small changes feel doable this week? Pair the number with context, then choose one low‑friction action you can repeat. Over time, those actions move the needle.

Conclusion

This BMI guide shows how to calculate your BMI, what the categories mean, and where BMI is most and least helpful. Combine it with body composition and waist measures to get a fuller picture of health context—and use tools that support sustainable habits.